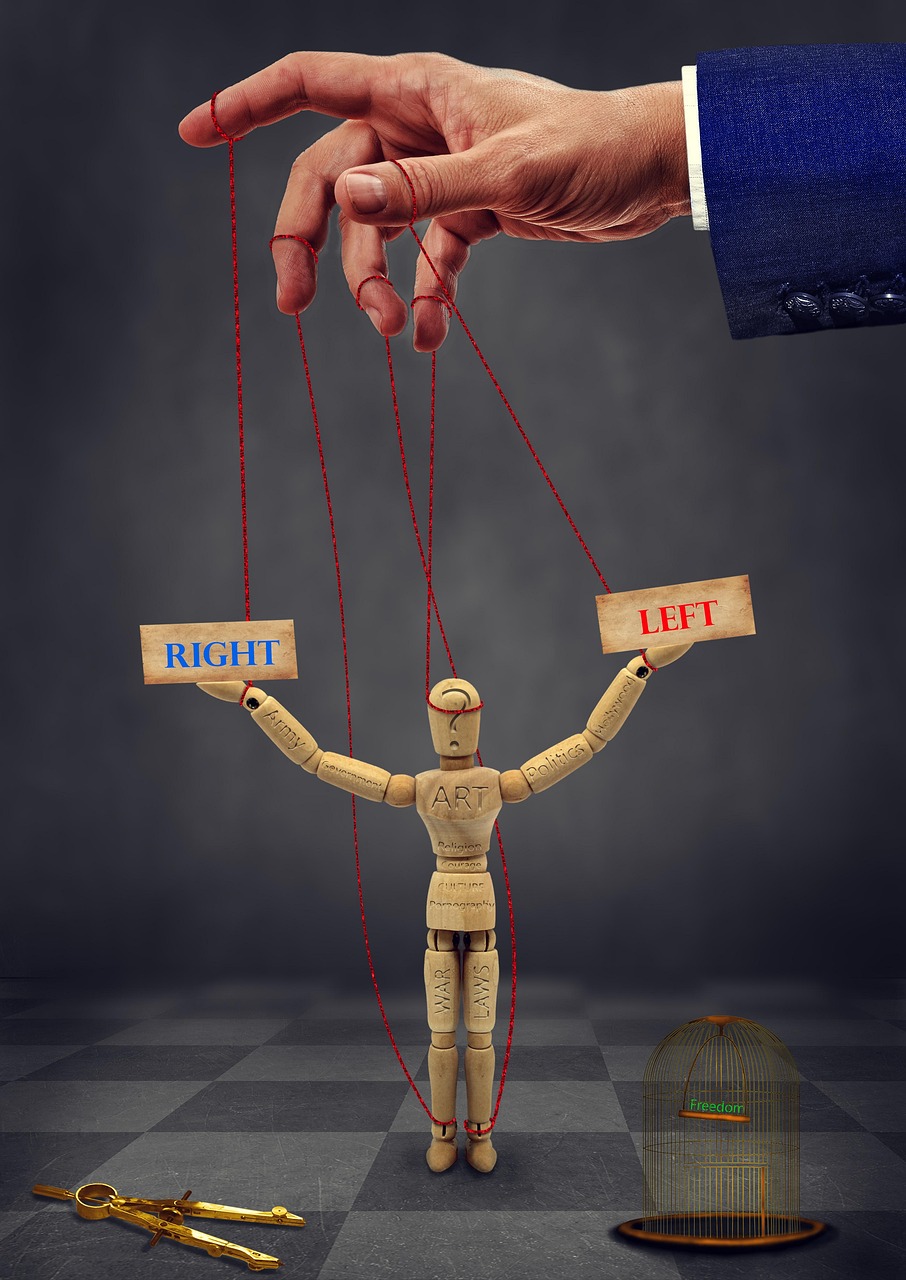

Democratic systems are commonly understood through the lens of elections and political power appears to be granted primarily through the ballot box. Yet this understanding is increasingly incomplete. In practice, many of the forces that shape public policy operate outside formal electoral mechanisms. Decisions about which issues are debated, which policies are considered viable, and which narratives dominate public discourse are often influenced long before any vote takes place. This influence does not always come from elected officials, but from individuals and organisations that hold economic, technological, or informational power without holding public office.

This essay examines how unelected actors can influence policy without electoral mandate. It argues that modern political power extends beyond institutions of government and into spheres of capital, infrastructure, and communication.

Rethinking Political Power Beyond Office

Political power is often equated with formal authority: the power to legislate, regulate, or enforce law. However, power also operates through less visible mechanisms such as agenda-setting, access, and narrative framing. Those can shape political outcomes without requiring formal decision-making authority.

Agenda-setting refers to the ability to influence which issues are considered politically important. If a topic never enters public debate or policy discussion, it cannot become the subject of legislation. Similarly, access to policymakers, through advisory roles, informal consultation, or proximity to political elites, can shape how problems are defined and which solutions are treated as realistic. Narrative power is equally significant: control over major platforms of communication allows certain actors to amplify ideas, frame debates, and normalise particular viewpoints. While this does not constitute direct policy-making, it influences the environment in which policymakers operate. Political decisions are rarely made in isolation from public opinion, media pressure, or perceived economic constraints. In this sense, power is not limited to those who hold office. It also belongs to those who shape the conditions under which political decisions are made.

It is true that in modern economies, wealth alone does not guarantee political influence. What matters is the ability to convert economic resources into structural leverage. This often occurs through control of infrastructure whether financial, technological, or communicative. High-profile international gatherings such as the World Economic Forum bring together heads of state, business executives, and institutional leaders in settings that are not formal legislative spaces but clearly influence global discourse and priorities. These forums do not pass laws, but they provide access, agenda-setting opportunities, and networked influence that operate outside electoral mechanisms. Their existence underscores how political influence increasingly emerges through proximity and shared environments rather than through electoral mandate.

Governments may hesitate to regulate sectors that are economically strategic, socially embedded, or politically sensitive. When private actors control systems that large populations rely on, their preferences can acquire political weight even in the absence of formal authority. This influence is typically legal. It does not require bribery or explicit lobbying. Instead, it emerges from asymmetries of dependence. When public institutions rely on private actors for investment, innovation, or communication, the boundary between economic power and political influence becomes blurred.

Crucially, this form of influence lacks the accountability mechanisms that accompany elected office. Unelected actors are not subject to electoral removal, parliamentary scrutiny, or constitutional limits in the same way as public officials. Yet their decisions can have political consequences.

Elon Musk: The Contemporary Illustration

The public prominence of Elon Musk offers a useful illustration of how unelected influence operates in practice. Musk does not hold public office, nor does he formally set government policy. However, his control over major companies and platforms places him in a position of significant structural influence.

Through ownership of a major social media platform, Musk has direct impact on the dynamics of public discourse. Decisions about moderation, amplification, and platform norms shape which voices are heard and which narratives gain traction. While these decisions are framed as private business choices, their political implications are substantial. In addition, Musk’s proximity to political elites and visibility within policy debates grant him informal access that most citizens lack. Public statements made by influential figures can shift market expectations, media agendas, and political priorities, even without explicit policy demands.

This influence is not absolute, nor is it uniquely held by one individual. Rather, Musk represents a broader category of actors whose economic and communicative power allows them to shape political environments without electoral mandate.

Why Unelected Influence Is Difficult to Regulate

Unelected political influence is challenging to address precisely because it does not fit neatly into existing regulatory frameworks. It is often neither illegal nor overtly political and actions taken in the name of business strategy, free expression, or innovation can nonetheless have political effects.

Traditional regulatory tools are designed to address lobbying, campaign finance, or direct corruption. They are less effective at addressing diffuse forms of influence that operate through markets and platforms. Attempts to regulate such influence risk accusations of censorship, overreach, or economic harm. Moreover, democratic institutions were largely designed for an era in which political power was more clearly bounded by the state. In an interconnected global economy, power is increasingly decentralised and mobile, making national regulation more complex.

But Still Influence Is Not Control

It is important to distinguish influence from control. Unelected actors cannot pass laws, enforce regulations, or override electoral outcomes. Elections remain central to democratic legitimacy, and public officials retain formal authority over policy decisions.

Additionally, public figures are entitled to participate in political discourse. Wealth or prominence does not negate the right to expression, nor does influence necessarily imply abuse. These arguments are valid, however, they do not negate the central concern. While unelected actors do not control policy, they can shape the range of options that policymakers consider viable. Influence operates upstream of decision-making, affecting priorities, constraints, and public expectations.

Democracy is not only about who decides, but about how decisions become thinkable in the first place. Elections remain a cornerstone of democratic systems, but they do not capture the full landscape of political power in contemporary societies. Policy is shaped not only by those who hold office, but by unelected actors who control capital, infrastructure, and communication.

The influence of figures such as Elon Musk highlights a broader structural reality rather than an individual anomaly. Modern power often operates without mandate, accountability, or clear institutional boundaries. Understanding this does not require rejecting democracy but it requires recognising it’s limits. As political influence continues to evolve beyond formal institutions, democratic systems face the challenge of reconciling electoral legitimacy with the realities of unelected power.

The question is no longer whether elections matter. It is whether they are sufficient to account for how power operates today.

Leave a comment