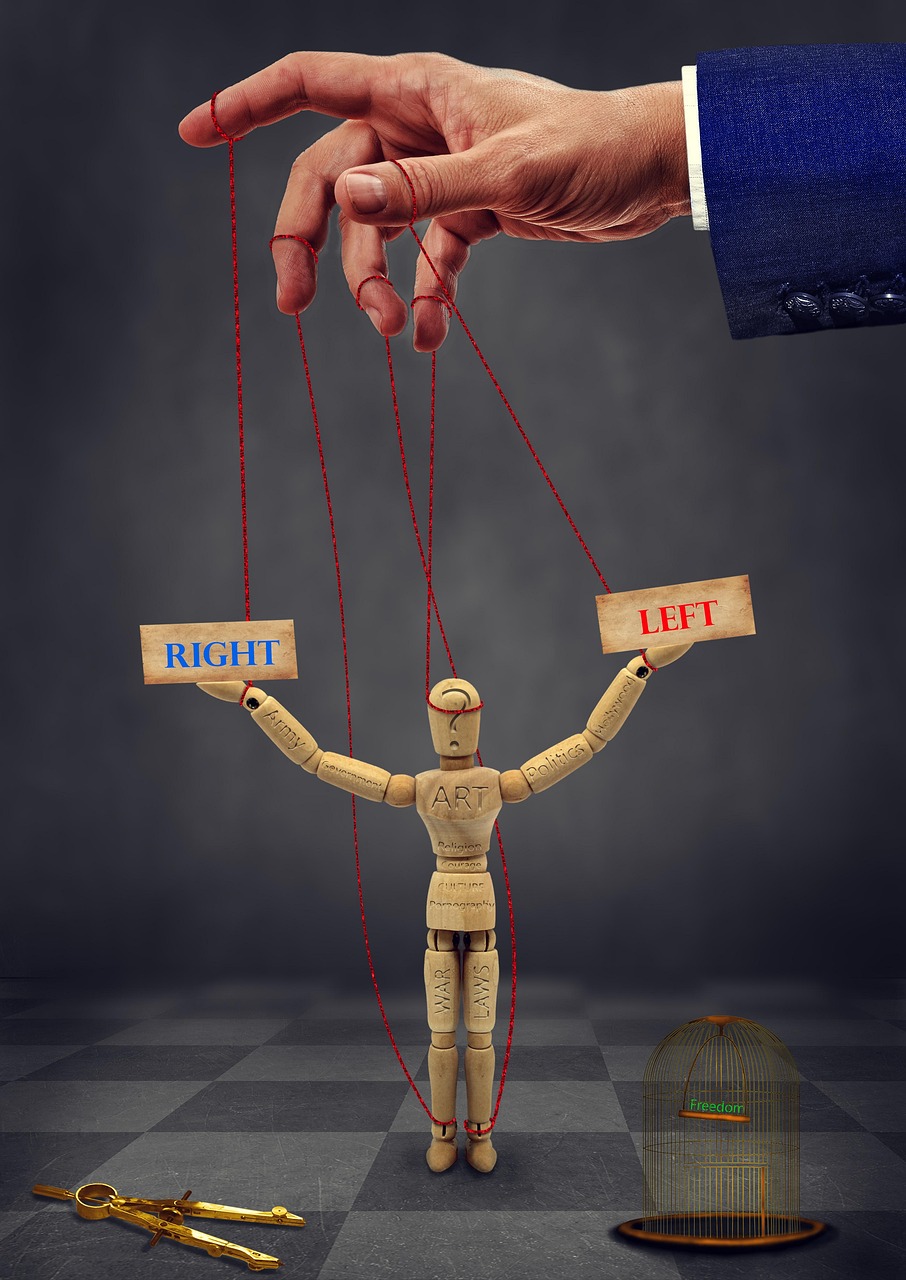

Political disagreement is often explained as a clash of values, information, or ideology. Individuals are assumed to arrive at their political beliefs through conscious reasoning in adulthood, shaped by debate, media exposure, and personal reflection. Within this framework, political orientation appears to be a matter of choice. However, a growing body of research suggests that political beliefs are shaped much earlier than commonly assumed. Long before individuals vote, join parties, or engage in public debate, their views on authority, fairness, responsibility, and social order begin to form. These early dispositions are closely linked to childhood experience.

Family environment, economic conditions, educational settings, and exposure to stability or insecurity influence how individuals perceive risk, trust institutions, and interpret social change. Rather than determining specific political positions, childhood experience shapes the lens through which political information is later understood. As a result, political disagreement often reflects differences in lived experience rather than differences in intelligence or moral intent.

This essay examines how early-life conditions influence political beliefs beyond conscious awareness. Drawing on research from political psychology, sociology, and economics, it argues that political orientation is not merely adopted in adulthood but is partially structured by childhood experience long before formal political engagement begins.

Childhood as a Site of Political Socialisation

Political socialisation refers to the process through which individuals acquire attitudes and assumptions about society, authority, and collective life. While schools, media, and peers all play a role in this process, family environment remains one of the most influential early factors.

Research consistently shows that children absorb implicit political cues through everyday experiences rather than explicit instruction. Exposure to parental authority, household stability, and economic security shapes expectations about how the world functions. For example, children raised in predictable environments tend to develop higher levels of institutional trust, while those exposed to instability often prioritise self-reliance or scepticism toward authority.

Importantly, these effects do not require political discussion within the household. Values related to obedience, autonomy, fairness, and risk are transmitted through routine interactions, discipline styles, and responses to stress. These early patterns influence how individuals later respond to political narratives about order, redistribution, freedom, and responsibility. Political beliefs, in this sense, begin forming well before individuals have the language to articulate them.

Economic Security in Childhood and Attitudes Toward the State

One of the strongest predictors of later political orientation is exposure to economic security or insecurity during childhood. This does not mean that individuals who experience hardship inevitably adopt a specific ideology. Rather, early economic conditions influence how people interpret the role and reliability of institutions.

Longitudinal research drawing on datasets such as the World Values Survey shows consistent associations between childhood economic stability and adult levels of institutional trust. Individuals raised in households with predictable income and access to basic resources tend to report higher trust in public institutions and greater tolerance for collective risk-sharing. By contrast, those exposed to prolonged financial insecurity often develop more sceptical attitudes toward systems perceived as distant, unreliable, or conditional.

Crucially, these differences are driven less by absolute income levels than by predictability. Children who grow up in environments where necessities are reliably met internalise expectations of continuity. Those raised amid volatility learn to prioritise immediate security and develop heightened sensitivity to risk. Later in life, these differences shape how political proposals are interpreted. Policies framed as long-term investments may appear credible to one group and risky to another, even when the factual content is identical.

Evidence from the British Election Study reinforces this distinction. Analyses show that early-life exposure to economic instability is associated with lower political trust and higher disengagement in adulthood, even after controlling for current income and education. This suggests that childhood conditions leave durable cognitive imprints that persist beyond later material improvement. These effects are probabilistic rather than deterministic. Adult experiences can reinforce, weaken, or redirect early tendencies. However, childhood economic environments provide the initial framework through which later political information is filtered.

Authority, Discipline and Political Intuition

Beyond economic conditions, childhood exposure to authority plays a central role in shaping political intuition. Authority in this context refers not only to formal power but to everyday experiences with rules, enforcement, and decision-making within families and institutions. Political psychology research indicates that early exposure to consistent and predictable authority is associated with higher tolerance for institutional power in adulthood. Conversely, environments characterised by arbitrary enforcement or inconsistent discipline tend to produce scepticism toward authority figures. These patterns are documented across multiple studies synthesised by organisations such as the Pew Research Center, which show that political attitudes often persist across generations.

Children do not consciously evaluate authority structures but they experience them. Whether rules are explained or imposed, whether punishment is predictable or arbitrary, and whether authority figures are perceived as protective or threatening all influence how individuals later respond to political concepts such as law, order, and governance.

These early experiences help explain why political disagreement frequently centres on interpretation rather than facts. Calls for stronger enforcement may be perceived as necessary stability by some and as overreach by others. Appeals to individual responsibility may resonate with those raised in environments emphasising self-reliance, while appearing dismissive to those whose early experiences highlighted structural constraint. These differences do not stem from ignorance or irrationality. They reflect learned expectations about how power operates in practice.

Childhood Socialisation and the Limits of Rational Debate

If political beliefs are partially shaped by early experience, this has important implications for how political disagreement is understood. Public discourse often assumes that disagreement results from misinformation or flawed reasoning. While information matters, it operates within pre-existing interpretive frameworks.

Research on attitude persistence suggests that once core political orientations are formed, new information is more likely to be interpreted through reinforcement than revision. This does not imply closed-mindedness. Rather, it reflects the cognitive efficiency of relying on familiar schemas established early in life. This helps explain why political debates that rely solely on facts and data frequently fail to persuade. When individuals disagree about the meaning of fairness, responsibility, or security, they are often drawing on different experiential baselines rather than different information. Rational argument alone cannot fully bridge these gaps because the disagreement is not purely analytical. Recognising this does not undermine democratic debate. Instead, it clarifies its limits as understanding the role of childhood socialisation shifts the focus from persuasion to comprehension.

Counterargument: Choice, Change, and Adult Agency

It would be misleading to suggest that childhood experience rigidly determines political beliefs. Many individuals revise their views significantly over the course of their lives. Education, social mobility, migration, and exposure to new environments all contribute to political change.

Research supports this flexibility. Studies show that major life events: entering higher education, experiencing economic mobility, or relocating to different social contexts, can alter political orientation. Adult agency remains real and meaningful. However, acknowledging agency does not negate early influence. Childhood experience does not function as a script, but as a lens. It shapes how new information is interpreted, which arguments feel intuitive, and which risks feel acceptable. Change is possible, but it often requires sustained exposure to conditions that challenge early assumptions. In this sense, political belief formation reflects an interaction between early structure and later experience rather than a simple choice made in adulthood.

Conclusion

Political beliefs are often treated as products of reasoned choice or moral alignment. Yet evidence suggests that they are also shaped by early-life experience long before formal political participation begins. Childhood exposure to economic security, authority, and stability influences how individuals later understand concepts such as fairness, responsibility, risk, and institutional trust. These early experiences do not determine ideology, but they structure the interpretive frameworks through which political ideas are evaluated. Recognising this shifts how political disagreement is understood. Differences in political belief are not simply failures of reasoning or information. They often reflect divergent developmental experiences within shared political systems.

Understanding politics, therefore, requires looking not only at what people believe, but at how those beliefs were formed: often long before individuals realise it themselves…

Leave a comment