Side hustles were once framed as a form of ambition. They were commonly understood as creative outlets, opportunities to test ideas, or ways to earn additional income alongside a stable job. In this framework, side hustles functioned as optional activities, pursued by individuals seeking growth rather than necessity.

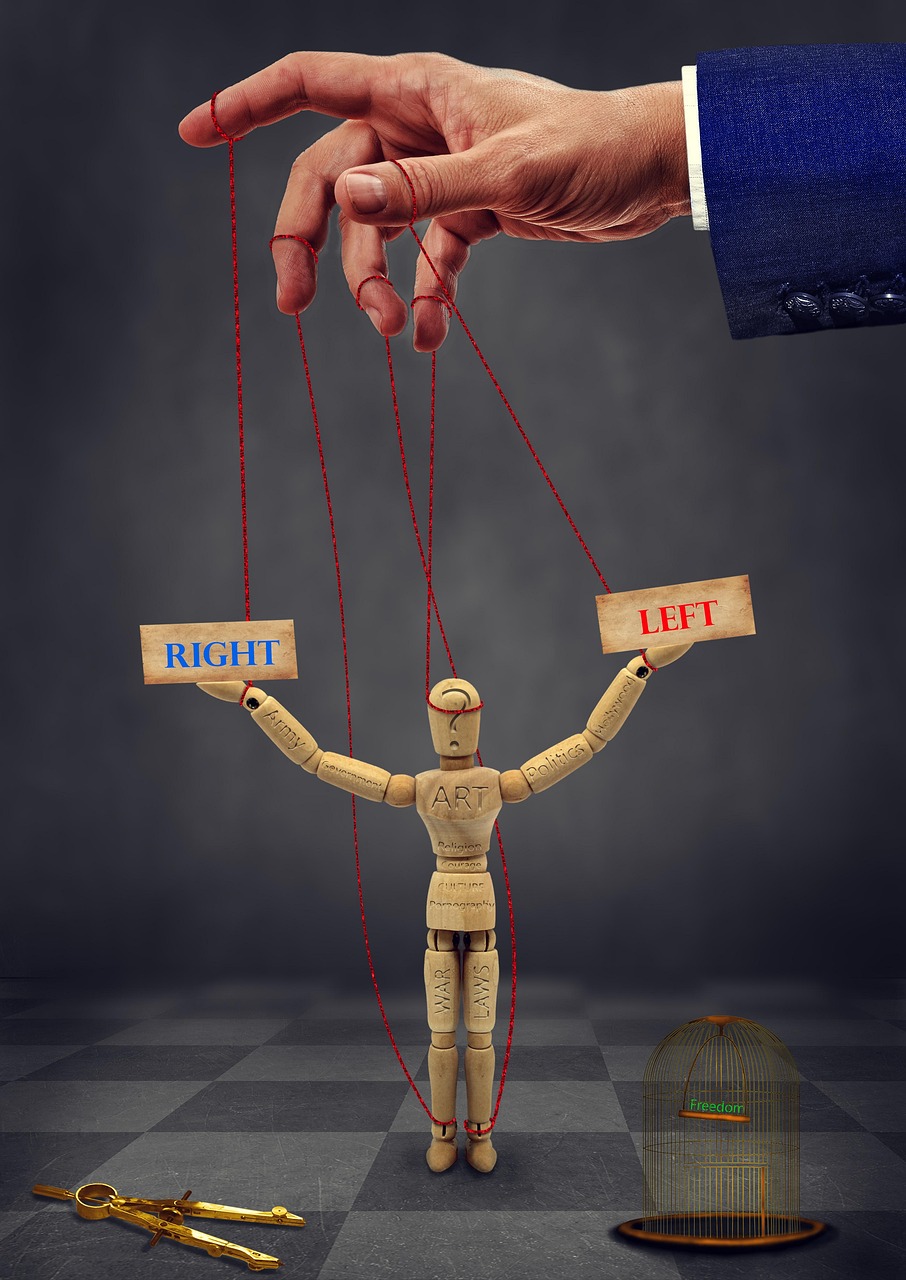

Over time, this narrative has shifted. For many people around the world, side hustles are no longer associated with freedom or self-expression. Instead, they have become a response to economic pressure. For some groups, particularly younger workers and those in insecure employment, side hustles were never a choice to begin with. Rent payments, utility bills, and food costs operate independently of personal motivation. As a result, what was once considered “extra” work has increasingly become essential.

In contexts where a side hustle represents a significant or primary source of income, the distinction between main employment and supplementary work becomes blurred. This shift marks a structural change rather than an individual preference.

The Original Promise of the Side Hustle

The appeal of the side hustle was grounded in the idea of autonomy. It was promoted as a way to escape rigid organisational structures and regain control over time and income. In the expanding digital economy, side hustles were positioned as symbols of independence and adaptability.

Social media amplified this message by presenting hustle culture as a lifestyle. Long hours, early mornings, and multiple income streams were framed as indicators of discipline and success. Importantly, this model assumed a stable economic base: a primary job capable of meeting essential living costs. Within this structure, side hustles could fund long-term goals, experimentation, or financial security.

This assumption has weakened. As living costs rise and employment stability declines, the conditions that once made side hustles optional no longer exist for many workers.

When Extra Income Becomes Necessary

Across Europe, and particularly in the United Kingdom, living costs have increased faster than wages. This imbalance has reshaped labour behaviour. Data from Employment Hero indicates that 42% of Gen Z workers juggle more than one job, often as a strategy to meet basic financial needs. Similarly, survey data from Boostworks shows that 57% of Gen Z and 71% of Millennials are considering taking on additional work to cope with rising expenses.

Several factors contribute to this trend. Housing shortages have driven up rents, inflation has increased the cost of essentials, and employment contracts have become more insecure. Public support systems have also failed to keep pace with these changes. As a result, income from a single job is often insufficient.

Historical comparisons highlight the scale of this shift. Among students, approximately 65% now engage in side hustles, compared to 38% in the 1980s. This change cannot be explained by cultural preference alone. It reflects a broader transformation in the economic environment. The same pattern appears among migrants, carers, and early-career workers. In these cases, multiple sources of income are not pursued for advancement, but for financial survival.

The Absence of Financial Buffers

The consequences of income insecurity are intensified by low levels of savings. In the UK, around one in six adults has no savings at all, while an additional proportion holds less than £1,000. These figures suggest that a significant share of the population lacks a financial safety net.

Without savings, individuals become more dependent on continuous income. This dependence reduces tolerance for risk and limits the ability to refuse work. In such conditions, side hustles cease to function as flexible opportunities and instead become mechanisms for maintaining basic stability.

The psychological implications of this shift are substantial. When individuals work to build something meaningful, effort is often associated with motivation and purpose. When work is required to prevent financial loss, it is associated with pressure. Rest becomes difficult to justify, and productivity shifts from being a strategic choice to a perceived obligation. The central concern is no longer future-oriented growth, but immediate continuity.

Time Poverty and the Illusion of Flexibility

Side hustles and zero-hours contracts are frequently marketed as flexible arrangements that allow individuals to control their schedules. However, evidence suggests that this flexibility is limited in practice. Research by the Trades Union Congress indicates that 84% of zero-hours workers would prefer more stable and predictable working hours. Only a small minority express satisfaction with the lack of security.

Further data shows that many zero-hours workers remain with the same employer for extended periods, despite the absence of guaranteed income. Two-thirds have stayed for over a year, and nearly half for more than two years. These patterns indicate constraint rather than choice. Workers may be contractually free to decline shifts, but financial necessity often removes that option in practice.

This dynamic produces time poverty. Individuals remain technically flexible while being economically bound. Over time, sustained exposure to this condition normalises exhaustion and obscures its structural origins.

When Side Hustles Stop Serving Long-Term Goals

As side hustles become increasingly tied to survival, traditional definitions of success lose relevance. The ability to cover basic expenses no longer reflects ambition or personal values. Instead, it reflects adaptation to economic conditions.

A critical question emerges in this context: whether a side hustle contributes to long-term stability or merely sustains the present. Indicators of imbalance include persistent fatigue, emotional detachment, limited progress despite sustained effort, and declining satisfaction with work previously found meaningful.

Recognising these signs does not imply that individuals can easily withdraw from such arrangements. For many, disengagement is not feasible. However, distinguishing between temporary survival strategies and long-term plans is essential. Treating survival mode as permanent risks entrenching instability rather than resolving it.

Conclusion

Not all individuals have the freedom to reduce working hours, change career paths, or prioritise personal interests. For those whose side hustles function as lifelines, this reality reflects economic constraints rather than a lack of ambition.

Survival should not be conflated with failure. Nor should constant productivity be mistaken for success. The more relevant question is not why individuals work multiple jobs, but why economic systems increasingly require them to do so in order to meet basic needs.

Leave a comment